COPYWRITING - On simplicity in writing and ideas

What is the one thing you want to say? What is the one thing you want to do?

What is it you want to say (write)?

I got this piece of advice from one of my mentors pretty early on when I was a junior copywriter. It was my first job at a boutique agency in Amsterdam. They just opened an office there, and though we weren’t a lot of people, the leadership had good connections, so we had great clients from the get-go—one of them being Nike. Learning to write copy for Nike pretty much from the beginning of my career is something I’m very grateful for, as I see it as somewhat of a benchmark in copywriting.

A lot of what I learned writing for Nike I apply to other brands and it always works. It’s on my list to soon write detailed case studies about the learnings, tips, and tricks when writing for the different brands I wrote for (the first one being Nike), so stay tuned. But for now, one of the most important ones is to always write in a single-minded way.

I was mentored by the ECD of the office, who had worked a lot for Nike global. She was very experienced in terms of leadership, but during our sessions, she focused heavily on copywriting—while always considering the bigger picture of what was being presented, how, and to whom.

Whenever I presented my copy, she always asked: What is the one thing you want to say?

She meant it quite technically. In every form of writing, there’s a hierarchy, and in her opinion, the most important thing should lead—or even be the only thing you're conveying. I’d say that, in advertising, I pretty much agree. Writing should be to the point and single-minded. When writing becomes more artistic—not just in creative writing but also for more storytelling-focused clients like those, e.g., in fashion—this doesn’t always hold true.

But for most brands, when thinking about lines, PR headlines, or even manifestos, what is the one thing you want to convey? And when you start adding things that are slightly different, do they actually add to that one thing, or do they distract? Do they push the narrative in a way it shouldn’t go?

Copy should never be cluttered because nobody really WANTS to read copy like they read a book or a beautiful poem. People may glance at copy, and when it’s great, maybe they smile and appreciate they accidentally read it (great job when you achieved this). This means people need to get it even when they read it from the corner of their eye; it needs to be single-minded.

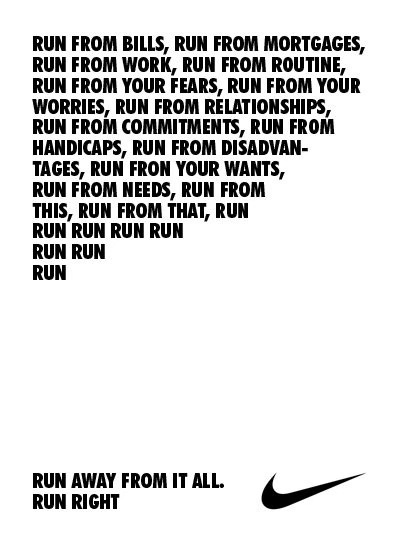

Nike running is a great example because, firstly, it’s always about running (which sounds obvious) but in the most direct and blunt way. They never say running indirectly. It’s always in your face RUN. Buuut secondly (less obvious), it’s always about one specific angle, like the above manifesto is about running away from it all. One concept all the way through, and there is no second angle or opinion on running mixed in somehow, like, perhaps, where you run to, when, and how. It’s strictly just running away, and that’s it.

Going through this exercise, how many angles (e.g., running away from, how running feels like, running at a certain time of the day, or whatever) under one narrative (running) are you touching upon, and do you want to cut back to tell one story or at least no too many stories at the same time?

What is it you want to do (produce)?

So, this same advice also applies to the conceptual side—when writing up or discussing ideas. Sometimes great ideas have all these elements in our heads, and we keep building on them—when we write them alone or brainstorm with a partner. We keep adding stuff. This CAN be great, but not always.

The strongest ideas are surprisingly obvious in a way that other creatives think; how didn’t I think of that? In other words so simple they are brilliant. But not lazy. It’s often expected but with a twist. From all the ideas I came across so far that really landed with clients, it was mostly this: obvious but somehow unexpected. It’s not as much of a contradiction in itself as it sounds. Think about what an obvious idea is, and then ask: Can I still make it great? Can I add a twist that suddenly makes it interesting?

Actually, I realized crafting beautifully complicated concepts (let’s call it that) is a very junior thing to do because juniors are motivated enough to make concepts beautifully complicated. I did the same and still catch myself doing this when I like a brief. When I’m eager and motivated, I want to express all these things in one idea because my brain is overflowing, and I want to do it all. And to be fair, that’s why juniors are hired to bring this unique, elaborate thinking to the table. In most cases, my elaborate, beautifully complicated ideas got cut down to something more simple (boring, I thought). It was frustrating, but they are meant to be cut down because clients tend to be scared of the beautifully complicated. Understanding this early on may ease some frustration, but you can also immediately do both: inspire your creative director/client with that beautifully complicated thinking but also deliver ideas that are simple and single-minded.

Now, there’s another moment when concepts often get complicated: when you’re in the later stages of the concepting phase, and a client asks you to combine concepts. Do yourself a favor: don’t just say yes in the heat of the moment. You might hate yourself later. Take your time to think about whether combining two concepts really works or actually weakens your favorite concept of the two. It’s ok to go back and say no; just say darlings needed to be killed.

Tips for recognizing when to cut something

If you’re not sure whether something needs to go, ask yourself:

Does this idea add to the one core message, or is it pulling attention away?

Could this idea work better as a separate project?

If I remove this, does the piece become sharper and more impactful?

It’s always better to have one clear, strong idea than to dilute it with unnecessary extras.

What IS IT you want to say or do?

Here’s a (somewhat) related piece of advice that I learned and wish I had applied earlier. Sometimes, we present a lot just to show variety or options. Some clients ask for a lot of routes and we just execute to get to that number. But don’t immediately present everything.

Remember, as a creative, you hold power. Present the ideas you WANT to present because if the work gets made and you actually like it, that’s soo valuable. I remember ideas I presented that made it to later stages, and I thought: Why the f did I present this? Now, it might get made, and I actually hate it. This will never go into my portfolio. Realizing this can be such a sad moment, especially if it’s actually for a client you were excited about at first. As a creative, you can be selfish and think about your portfolio first (just don’t tell your client). It might be more difficult to present a variety of ideas that you all like, and of course, it doesn’t always work, but just don’t present something that you might actually find awful just because you think your client might like it. Unless you don’t care.

So before you put your work out there—whether it’s a headline, concept, or full presentation— ask: What’s the one thing I want this to do? If you can answer that clearly, you’re already ahead. Keep it focused, keep it intentional, and don’t lose sight of the creative power you bring to the table. This was a bit of a ramble, but thanks for reading ❤️

You found this interesting, but you’re also slightly confused because you’re not 100% sure what a copywriter is? Read this:

You liked reading that Nike manifesto and want to read more manifestos? Two examples here:

strong read.